North Cascade Glacier Climate Project 2006 Field Season- Our 23rd Field Season

For the 23rd year in a row I found myself arriving in the North Cascades in late July to begin several weeks of glacier research. The field team consisted of Erik Budsberg a geology student at WWU, Tom Hammond a network engineer from UW, Ben Pelto my son and myself. Arriving at SeaTac airport at noon, Erik met us and we headed for Monroe and the Safeway for provisions, lots of oatmeal, lipton rice and noodles, bagels and dried fruit. By three we were streamside on the North Fork Skykomish River packing up and waiting for the cool of the evening for the hike to the alpine country. Having woken up 18 hours before, the 2700 foot ascent in three miles on the Blanca Lake Trail, was just what the doctor would never order. Ben and I collapsed in the tent no need for a snooze button. 21 hours after waking up.

In the morning we packed up camp, forded Troublesome Creek, which is knee deep and nearly 100 feet across at the exit from Blanca Lake. This lake is something to behold, and you get to do just that as you struggle around it on a obstacle ridden climbers trail. We set up camp at the far end of the lake and after a quick dip, headed uphill to the Columbia Glacier. The glacier is in deep cirque with substantial walls on all sides. The upper basin of the glacier is nearly flat and viewed from a distance the glacier appears much smaller than it is. It is still a mile long. The glacier had better snowcover than the previous three years, but that was not saying much. We spent the next two days probing this snowpack in 130 locations determining that the glacier will lose about a meter of thickness this year. The terminus had retreated 15 meters since last summer. We practiced self- arresting and some steep snow climbing on the second day where good runouts existed in preparation for steep slopes with less than perfect runouts. We also bagged our first pass, Monte Cristo Pass, utilizing a nice snow cave past the crux. The pass was in clouds mostly but one mountain goat showed its traversing skills below us. We patiently awaited until evening for the parting of the surface whiteout to complete our measurements, the laser ranger does not work well in fog.

In the morning we packed up in light drizzle and hiked out headed north to Mount Shuskan. The forecast was for some showers the following day and then cool but cloudy conditions for several days. Thus, that evening we found ourselves with the backpacks back in place, hiking in the popular trail to Lake Ann below Mount Shuksan. We found that despite the weekend, this is only a popular spot with good weather. That night the shower began and was awfully persistent and hard for 14 hours to qualify as a shower. We sat it out and enjoyed some interesting lighting on Shuskan and the new snow on the face of Shuksan, as evening came and the rain finally ended. The next day was double time and after all the tent time this was not an issue. We ascended to Lower Curtis Glacier at 6 am. It is best to survey the terminus before it gets warm and small ice and rockfall ensues. This glacier has proved to have retreated 151 meters since 1985, and 14 meters in the last year. The terminus ice face is still over 100 feet high indicating the thick vigorous nature of the glacier. The glacier will lose a bit under a meter of thickness this year.

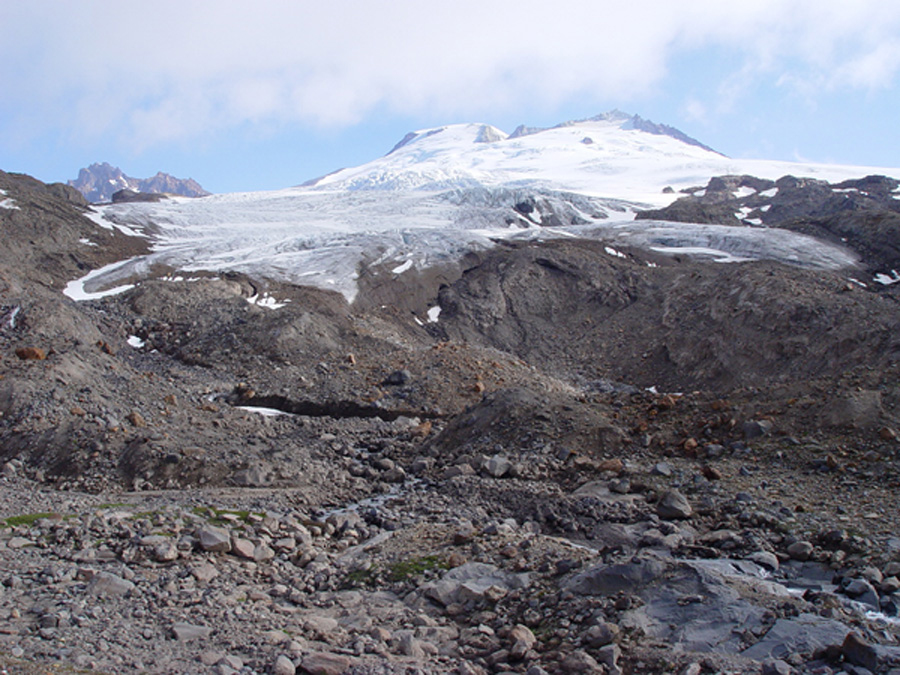

The following morning, heavy frost, covered our gear in camp, water bottles considerably frozen. Such frosts used to be common place, but this was my first at this time of the year this century. We traversed the Sholes Glacier to the Portals, another high pass bagged, and descended the Portals Glacier onto the Rainbow Glacier draining a saddle on the northeast side of Mount Baker. We then descended the Rainbow to the terminus at 4200’ , some 2000’ below our camp. The glacier has a grand canyon carved into it by a surficial stream. The canyon is up to 100’ deep in places and ends in a Moulin that could easily fit an SUV. Lunch near the terminus was followed by the 2400 foot climb to the top of the glacier broken by measurements every 100 feet allowing us to catch our breath. The snowpack once it is over 3 m deep, is measured by dropping a measuring rope into the crevasses. Thus, we do look demented going from crevasse to crevasse. At the top of the glacier where it joins the Mazama Glacier we could see considerable steam issuing from the Dorr Steamfield, the snowpack here from last winter was 5 meters deep. I had never seen such a plume on the north side of Mount Baker. Tthe descent off the top of the Rainbow last year was steep blue ice, crevassed, and quite deadly; this year the area was buried under 4 meters of snow. Last year we came off beaten, cautiously picking our way through a mine-field. This year we glissaded the 40 degree slope with the joy of a summer ski. We were carving telemark turns, whoops of joy echoing off the sheer cliff adjacent to the ice-fall, the smell of sulphur dioxide strong in the air. I guess just another reason to like a healthy snowpack, and eschew those behaviors which compromise our water supplies.

Dog tired after 10 hours on the trail we traversed the three miles to camp losing and gaining as little elevation as possible. The Rainbow and Sholes Glacier were the only two with decent snowpack in the North Cascades.

Hiking out in the morning we circled the mountain and hiked in that evening to Easton Glacier on the south side of Mount Baker. We were joined by Greg Pierce an artist in residence at the National Park. We camp right near the terminus of the glacier, well below the gaze of the Railroad Grade, this site features a truly glacial wind, keeping all bugs away. The Easton Glacier had been getting steeper each year at the terminus of late, however, last summers retreat was so extensive 30 meters, that the glacier had retreated onto a gentler slope allowing easier access. The lower icefalls also proved easier to navigate through. We traversed the glacier laterally several times measuring changes in glacier thickness. The next morning we ascended the Easton Glacier measuring snowpack first by probing and then in crevasses until we were stopped by a wide sweeping crevasse near the top of the glacier. We then descended finding more crevasses as we descended. After not seeing anyone on the other glaciers, Easton Glacier had plenty of traffic, including a tired party of three after fourteen hours on the trail. They still had crampons on descending the mush, leaving there crampons balled up. The night had been clear, and so was the day and they had wands, unused, and they were still lost on the glacier. They used an interesting rope technique, with 25 feet between them including a good six feet of slack, they would approach a crevasse, give a flick to the rope laying on the snow surface and leap-step across onto there balled up crampons, only twice in our brief observation managing to step on the rope. The snowpack was down about a meter from what is needed for the Easton Glacier to maintain its balance for the year.

Our last stop was Mount Daniels. The Cle Elum River was high indicating a the wet spring and decent snowpack that had existed. A swim in the river demonstrated that the current was stronger as well. We waited until 6 pm to hike in, it was still not that cool. The mosquitoes greeted us in number as we reached the first of the lakes along the trail. The rest of the hike to our Cathedral Rock campsite featured few stops do the mosquitoes. We tacked on an extra distance to camp higher, no bugs hopefully, hiking under the rising moon. Morning revealed that the mosquitoes had migrated uphill to this camp which had always been my bug safety camp. Snowpack proved less here than further north and west. The Ice Worm Glacier, the smallest had retreated enough in the last year to expose a new alpine tarn at its terminus. We climbed on some small icebergs in the lake and took probably the first ever swim in this small lake. The Daniels Glacier having retreated 443 meters since 1985, has gotten even steeper and has more melt out crevasses than before. It took considerable effort with probing for crevasses to safely reach the high pass onto Lynch Glacier. We descended Lynch Glacier to the terminus above Pea Soup Lake. This glacier has not retreated in length that much in recent years, but the western third has been separated by a rock rib. Snowpack which should be in excess of 3.5 meters in the upper reaches of the Lynch barely averaged 2 m. After completing the probing and crevasse measurements, we crested the top of the Lynch Glacier up a steep cornice onto the saddle and climbed quickly to the top of the main peak of Daniels, out one and only summit to add to the list of passes and glaciers. On this day we had the mountain to ourselves. We could see from Mount Hood to Mount Baker, the views eastward were as clear as I have ever seen. Foss Glacier on Mount Hinman had another poor year, and is clinging to life, 1/3 of its 1985 area remaining. Mount Daniels after a snowy winter like much of the Cascades, and even a wet spring according to Daryl and Ann Nelson who man the Fish Lake Forest Service Cabin, still managed to lose more than usual to the brutal heat of July. The Mount Daniels Glacier have lost an average of 10 meters of thickness from 2001-2006. Given the 30-40 meters of thickness, this is 25-33% of the glaciers lost in this short period. On the other hand thick glaciers like the Columbia, Lower Curtis, Rainbow, and Easton Glacier only slight less thickness but were twice as thick to begin with.

Our last stop was Mount Daniels. The Cle Elum River was high indicating a the wet spring and decent snowpack that had existed. A swim in the river demonstrated that the current was stronger as well. We waited until 6 pm to hike in, it was still not that cool. The mosquitoes greeted us in number as we reached the first of the lakes along the trail. The rest of the hike to our Cathedral Rock campsite featured few stops do the mosquitoes. We tacked on an extra distance to camp higher, no bugs hopefully, hiking under the rising moon. Morning revealed that the mosquitoes had migrated uphill to this camp which had always been my bug safety camp. Snowpack proved less here than further north and west. The Ice Worm Glacier, the smallest had retreated enough in the last year to expose a new alpine tarn at its terminus. We climbed on some small icebergs in the lake and took probably the first ever swim in this small lake. The Daniels Glacier having retreated 443 meters since 1985, has gotten even steeper and has more melt out crevasses than before. It took considerable effort with probing for crevasses to safely reach the high pass onto Lynch Glacier. We descended Lynch Glacier to the terminus above Pea Soup Lake. This glacier has not retreated in length that much in recent years, but the western third has been separated by a rock rib. Snowpack which should be in excess of 3.5 meters in the upper reaches of the Lynch barely averaged 2 m. After completing the probing and crevasse measurements, we crested the top of the Lynch Glacier up a steep cornice onto the saddle and climbed quickly to the top of the main peak of Daniels, out one and only summit to add to the list of passes and glaciers. On this day we had the mountain to ourselves. We could see from Mount Hood to Mount Baker, the views eastward were as clear as I have ever seen. Foss Glacier on Mount Hinman had another poor year, and is clinging to life, 1/3 of its 1985 area remaining. Mount Daniels after a snowy winter like much of the Cascades, and even a wet spring according to Daryl and Ann Nelson who man the Fish Lake Forest Service Cabin, still managed to lose more than usual to the brutal heat of July. The Mount Daniels Glacier have lost an average of 10 meters of thickness from 2001-2006. Given the 30-40 meters of thickness, this is 25-33% of the glaciers lost in this short period. On the other hand thick glaciers like the Columbia, Lower Curtis, Rainbow, and Easton Glacier only slight less thickness but were twice as thick to begin with.

The glaciers around Cascade Pass Yawning and Cache Col also featured poor snowpack, leading to a continued thinning of these two north facing glaciers. The start of the Ptarmigan Traverse is used to reach these glaciers, and this trail seems less used of late, maybe do the hordes headed for Eldorado and Inspiration Camps.

The glaciers around Cascade Pass Yawning and Cache Col also featured poor snowpack, leading to a continued thinning of these two north facing glaciers. The start of the Ptarmigan Traverse is used to reach these glaciers, and this trail seems less used of late, maybe do the hordes headed for Eldorado and Inspiration Camps.

The Mount Daniels Glacier have lost an average of 10 meters of thickness from 2001-2006. Given the 30-40 meters of thickness, this is 25-33% of the glaciers lost in this short period. On the other hand thick glaciers like the Columbia, Lower Curtis, Rainbow, and Easton Glacier only slight less thickness but were twice as thick to begin with.

A quick visit to the glaciers in late September identified unusually high ablation from mid-August- mid- September. A glacier needs about 70% snowcover at the end of the summer to be in equilibrium. Columbia Glacier had 25 % snowcover, Easton Glacier had 40% snowcover, Rainbow Glacier 50% snowcover, Ice Worm Glacier 0% snowcover, Lyman Glacier 25% snowcover. Fortunately the last two weeks of the month were cool, our observation on the week of Sept. 20th indicated new snow cover on most of the glacier areas. At right is Ice Worm glacier (Tom Foster photograph) in early October with minimal remaining snowcover from the summer season.

A quick visit to the glaciers in late September identified unusually high ablation from mid-August- mid- September. A glacier needs about 70% snowcover at the end of the summer to be in equilibrium. Columbia Glacier had 25 % snowcover, Easton Glacier had 40% snowcover, Rainbow Glacier 50% snowcover, Ice Worm Glacier 0% snowcover, Lyman Glacier 25% snowcover. Fortunately the last two weeks of the month were cool, our observation on the week of Sept. 20th indicated new snow cover on most of the glacier areas. At right is Ice Worm glacier (Tom Foster photograph) in early October with minimal remaining snowcover from the summer season.