North Cascade Glacier Climate Project 2002 Field Season:

Our Twenty-Second Field Season

After a very dry winter of 2000/01, the 2001/02 winter featured plenty of moisture. Periods of sustained snowy weather were interrupted by several warm rain-melt events, the first On January 4-7. We visited Easton Glacier in early January and found 6 meters of snow covering the terminus of the glacier. Cooler snowy weather dominated January and early February. Another warm spell…. The arrival of spring was gradual. We were going to be collecting the usual information on glacier mass balance, terminus position and mapping the surface profile of the glacier. In addition, we were sampling each glacier on our survey transects for glacier bugs. Assessing both the habitat and the populations.

Ed (the Dude) Blanchard, Paula Hartzell and Mauri Pelto ascended to the Columbia in late July to find good snow still around Virgin Lake before the descent to Blanca Lake. There were still some floating ice islands in Blanca Lake covered with large downed trees. Obviously a mammoth avalanche had swept onto the lake during the winter. The Columbia Glacier itself was buried quite deeply in snow. Particularly the north side of the glacier had received unusually large avalanching from the south facing wall of the basin It was clear from the mature trees snapped of in the area by the hundreds that a once in a generation sized avalanched had swept down from Kyes Peak. Columbia Glacier had no exposed ice and even at the end of the melt season had gained nearly 1 m of thickness during the year. We also saw the first mountain goat we had ever seen near this glacier.

Our next stop was Easton Glacier. The weather had deteriorated and for three days we dodged rainstorms-snowstorms as best we could. We were joined by Bellingham Herald report Erica Pizillo and photographer Jay on our first day. We measured the terminus retreat of the glacier at 315 meters since 1990. A sustained blizzard above 6000 feet on August 4th, forced on back to camp. Snowpack depths were slightly below 6500 feet, and substantially above average above 6500 feet. This suggests some warm precipitation events that yielded rain below and snow above this point.

The rain had not let up as we hiked into the Lower Curtis Glacier. We found an old growth tree to hide under and stay dry while cooking dinner, though our tent had to be set in the rain. The Lower Curtis Glacier has retreated little in the last 2 years, after retreating 10 m/year from 1992-1998. Avalanching was not unusually high on this glacier and its mass balance was only slightly positive. The poor weather and snowcover at Lake Ann resulted in the area being deserted.

Shuttling back to Austin Pass and out the Ptarmigan Ridge Trail we camped at Camp Kiser. A coyote’s howling helped put us to sleep the first night. The Rainbow Glacier was nearly completely snowcovered with 1 m more snow than most years. At the terminus which continues to thin, and lose crevassing, we ate lunch. Our entertainment was a trio of mountain goats ascending toward Lava Divide. One young goat had a few stumbles, and the group retreated several times before finding a good route toward the snow and rock divide, leaving any forage behind. Their purpose I do not know. They did not observe us. Once again we had the ridge The terminus has retreated 390 m since 1984, but appears to be thicker and less prone to rapid retreat.

With the weather showing a fairer side we headed for Glacier Peak. We chose to go in via the North Fork Sauk route over Red Pass instead of via Kennedy Hot Springs. The North Fork trail is through beautiful old growth for the five miles along the river to the beginning of the swithchbacks. It is a grueling ascent from here to the PCT back and forth across the same avalanche chute. This avalanche path had experienced a huge avalanche, which had obliterated the trail. Somehow the trail crew in the best effort I have ever seen, had restored the trail, during the previous month. Literally thousands of trees were felled, most in the 30-50 year age bracke, suggesting this was the first slide of this size in more than a generation. The slide starts at the ridgeline above the PCT at 6500. Alpine meadows dominated by slipper grass instead of heather dominate to 5000 feet. The alpine meadows are the largest I have seen in the North Cascades. After crossing the pass we descended to the Whitechuck River, and then followed it upstream to the lake near the end of the Whitechuck Glacier.

On the USGS or green trails maps for the area the Whitechuck Glacier has two lobes. Both are nearly a mile long and join near the terminus. In 1995 the northern lobe was stagnant ice with no retained snowcover, and was only a half mile long. In 2002 the Northern half was gone. Instead of an ice filled valley there was a boulder filled basin. The southern lobe of the glacier is thinning slowly, and retreating, but only 3-5 m per year.

The two new lakes that formed at the end of the White River Glacier are continuing to expand, as the glacier continues a slow retreat of 4-7 m/year. It is an easy traverse from the Whitechuck Glacier summit onto the head of the White River Glacier.

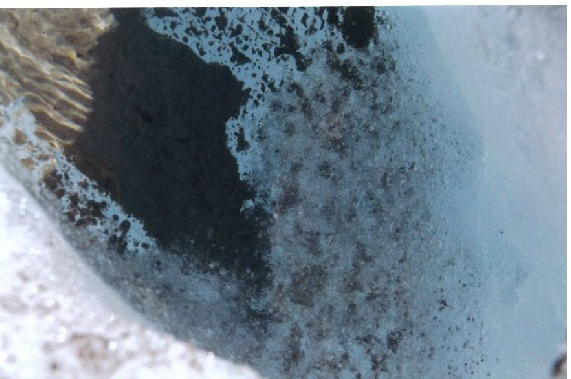

To reach one of the largest and longest North Cascade glaciers we had to ascend the Whitechuck and the White River Glacier. We proceeded to survey a longitudinal profile down the center of the glacier. It was 4 pm by the time we finished at the terminus, now six miles from camp, with at least a 2000′ climb. The glacier had retreated 40 m since 1995 expanding the terminus lake. We exited north onto the Suiattle Glacier after ascending the lower third of the glacier. The traverse across the Suiattle Glacier, it is now 6 pm looked endless. The mile plus long ascending traverse in fact took an hour in our tired state. But we were amazed at the sheer numbers of ice worms. The glacier was shaded by now as it is east facing and we were observing on a consistent basis at least 2600 ice worms per square meters. Given the area of 2.7 km for this glacier that yields a population of 7 billion ice worms. This one glacier has more ice worms than people inhabit the earth. For more information on ice worms examine our research web page. After crossing glacier gap we had a two mile slog to camp across the now glacier devoid north Whitechuck Basin. The rocky way was much slower and was not completed until dark. The most interesting observation of the day was the emergence of the ice worms 10 minutes after the sun went behind Glacier Gap. Without much variation the average population which we were counting was 3000 per square meter. For a glacier with an area of 3,000,000 square meters that is a mere 9 billion ice worms.

The next day we returned to the Suiattle Glacier and ascended from its retreating terminus to the head of the glacier and the Kololo Peak summit area. From the summit we descended to the Whitechuck Glacier and camp. The next day after a final survey of the terminus area of the Whitechuck Glacier we descended to the North Fork of the Sauk River passing a large boy scout group on the PCT. It had been a long 5 days covering 16,000 vertical feet and 50 miles.

We circled the mountains to Cle Elum and Mt. Daniels. Bill Prater had emplaced stakes in the Ice Worm Glacier a month earlier. The average melt through July and August had been 7.5 cm. The Ice Worm, Lynch, Foss and Daniels Glacier all had good snowpack, but barely above average. The hikers were numerous, and the conditions windy during the entire visit to Mt. Daniels. Both the number of deer and goats seems to be reduced in the area, possibly due to more hikers and climbers.

The glacier with the highest mass balance had been the Columbia Glacier. The glacier with the lowest mass balance had been the Rainbow Glacier on Mt. Baker.